As Skoltech continues to increase its global prowess through publications in major international journals and academic mobility programs, it has come to attract an increasing number of students, researchers and faculty members from abroad.

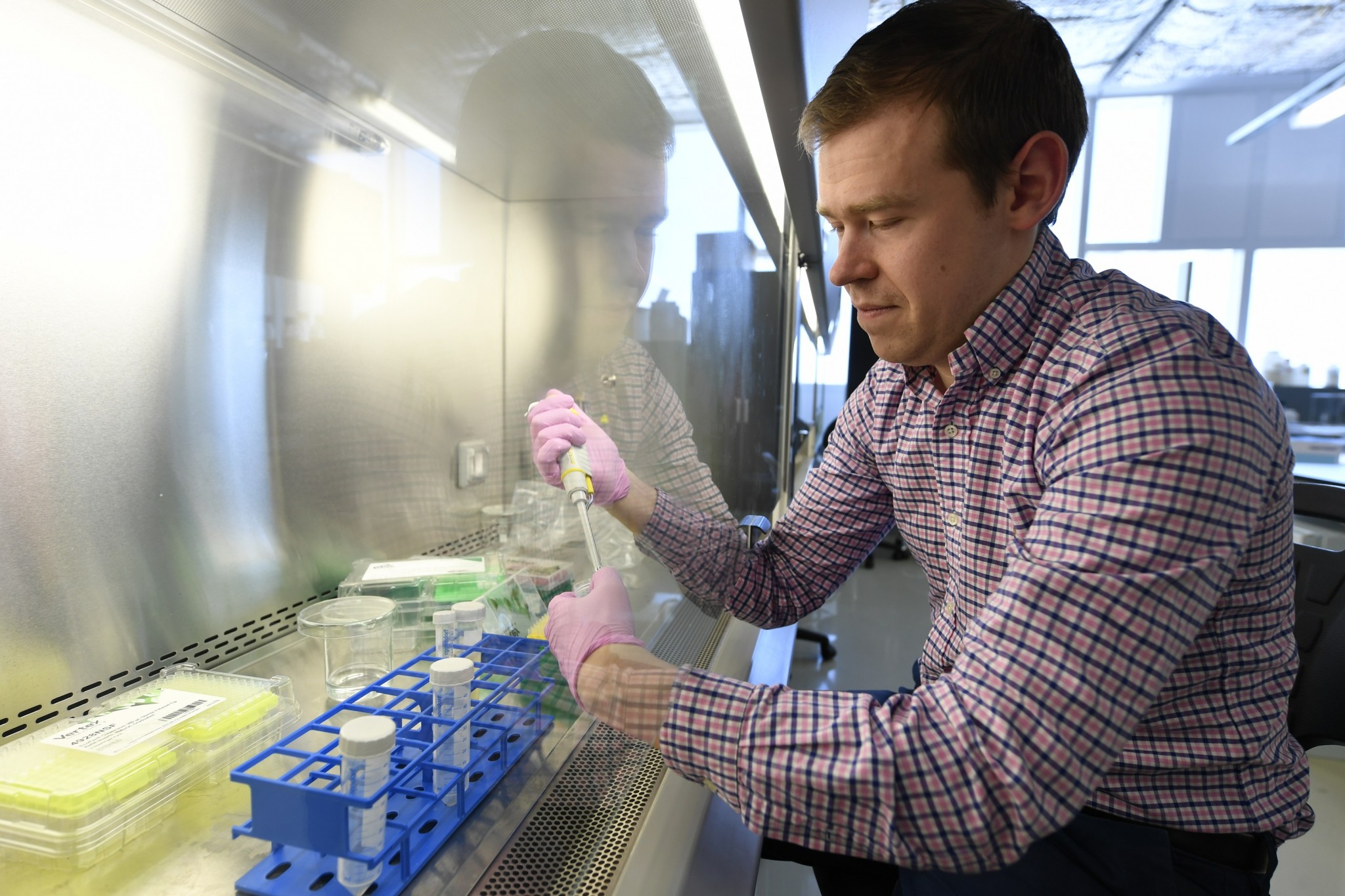

This term, two young researchers have decided to take a break from their British universities to spend time working in the laboratory of Skoltech’s Center for Data-Intensive Biomedicine and Biotechnology (CDIBB).

Nathaniel Holman is currently pursuing his PhD studies at the University of York, while Luis Wyss is a Biochemistry undergraduate at Imperial College London.

Citing his own experience, Professor Konstantin Severinov, Director of CDIBB, said that he believes scientific exchanges can be invaluable for young scientists.

“Back in the eighties I did a part of my thesis work as an undergraduate at Moscow State University in a lab at Bristol University (UK). This was pretty much a transformative experience that definitely influenced my scientific career, had an impact on my research style and set up some life-long collaborations and friendships. I am thus a strong believer in the value of mid- to long-term scientific exchanges involving young people,” he said.

He added that one aspect that truly sets Skoltech apart is its wealth of academic mobility programs, which allow MSc and PhD students to conduct research in labs abroad, noting that he is thrilled to see that this program has begun to result in foreign students heading to Skoltech.

“Up until very recently, these mobility programs were largely unidirectional due to the lack of lab facilities on our side. This is finally changing, so with the opening of [CDIBB’s] molecular biology lab at the Skolkovo Technopark, we decided to actively promote ‘reverse’ mobility to allow students from abroad to do projects here with our students. The initiative comes from our students who, after completing their mobility projects, establish collaborations that they can now take one step further by inviting colleagues and doing further joint research here. So far, things are going well with both Nathaniel and Luis and we plan to extend and expand the reverse mobility program in the future. I am convinced that international diversity is an absolutely essential ferment for scientific creativity that helps things get done and makes life in the lab and outside of it more interesting. We are lucky that Skoltech is a place where this can be implemented,” he said.

We caught up with Holman and Wyss to learn more about their experiences with Skoltech, and in Russia in general.

What brought you to Skoltech?

Holman: During the second year of my PhD program we had a visiting student from Skoltech – Artem Isaev. He’s working on a phage defense system in E. Coli and in our lab we look at phage defense systems in Streptomyces, so he wanted to come to the lab of my PhD supervisor to gain some experience.

I was very impressed with him. He worked very hard. We both worked long hours and became very good friends. I said to him that as part of my PhD, I have the option to do an internship and that I wanted to work in a foreign country because I’d never worked abroad before and thought it would be useful. He said there could be an opportunity for me to come to Skoltech for a few months, and that’s where it all started.

Artem went back to Russia, and I decided to come visit him. During the visit I went to Skoltech and asked if I would be able to do an internship, and everything just moved from there. Skoltech and our supervisor, Professor Severinov, were very accommodating and enthusiastic.

Wyss: Two years ago I did an internship over the summer at the Institut Pasteur in Paris, and at the same time Ekaterina Savitskaya, who is from the CDIBB lab, was there, and after a while she asked me if I was interested in doing another internship at Skoltech at a later point in time.

I realized I would have some time available this spring, so I contacted her a few months ago to ask if this would still be a possibility.

The lab here and the one at Institut Pasteur are both working on CRISPR systems. We’re not doing the same thing obviously, but the methods do not differ greatly, so indeed it turned out to be possible and now I’m here.

What are you working on at the CDIBB lab?

Holman: I’m working on a joint project with Artem Isaev. Soil-dwelling bacteria, particularly bacteria of the Streptomyces family, make a lot of natural products including antibiotics. Indeed, the majority of antibiotics used in the clinic that patients rely upon are made by bacteria that live in the soil.

In the case of these interesting bacteria, in order for us to be able to extract the antibiotics and other natural products that they make, we have to be able to manipulate them genetically.

A typical method we use is transformation. But there are a lot of bacteria that are not easy to genetically manipulate using common approaches like transformation. This is significant because if we can’t manipulate the bacteria, our ability to access the natural products they make is extremely limited. These importantly aren’t just antibiotics – they could be anti-cancer agents, or anti-inflammatory drugs.

So Isaev and I are working on a project where we can use viruses called phages that can be used to infect bacteria. We can engineer these phages to specifically recognize and infect strains of bacteria, and then finally introduce DNA (also designed and modified by us in the lab).

We can use this phage based engineering in two exciting ways. The first way is to manipulate existing biosynthesis pathways to make them function more efficiently. Secondly, this approach could be used to introduce completely novel natural product biosynthesis pathways, potentially allowing completely new antibiotics and natural products to be produced.

To summarize, we really want to have an optimized phage-based engineering protocol for the manipulation of natural product production.

This project is connected to a prestigious grant Isaev received. I’m only here for three months, so even though we want to make as much progress as we can while I’m here, the research will of course continue after I’ve left. That said, I’m hoping that even when I’m back in York, I can still continue some of the research.

We want to get as much done as possible over the next few months, but scientific research inevitably takes longer than planned. So we’ll see what happens, but we hope that we can get some good results and then publish.

Wyss: My project is a bit of a briefer project than Nathaniel’s because I’m only around for about a month.

I’m working on CRISPR systems, which are basically immune system for bacteria that consist of two parts. First, when a genetic intruder known to the cell enters a bacterium, the bacterium destroys the genetic material of the attacker. This is called CRISPR interference and has already been researched extensively.

In the second part of a CRISPR system, the bacterium finds out what is intruding and remembers its genetic fingerprint for the future, so in case of a subsequent attack, it can identify the attacker and defend against it.

What I’m interested in is how the bacteria actually get this information, enabling them to remember in the future what has been attacking them. This factor is actually less well understood. So here at Skoltech I’m trying to elucidate the mechanism by which the bacteria are able to take up these small pieces of DNA from the intruder and save them in their own genomes, so that they can recall this information in the case of a future attack.

How do you find the CDIBB lab facilities?

Holman: This is a very well equipped and modern lab. The equipment we’re using is all new and I have everything here that I need for my research. When you have everything you need, you don’t have to waste time; you can just get on with it. This is especially important when you’re only here for three months, time is of the essence, so the fact I’ve been able to start my work right away is great.

Wyss: I find it to be quite similar to other top research labs I’ve worked in in Western Europe. The lab is well equipped, roomy and bright and has access to next-generation-sequencing facilities. Ordering reagents may not be particularly fast, but that is hardly Skoltech’s fault and the situation will surely improve over the coming years. In addition, close collaboration with other laboratories in Moscow opens up new possibilities.

Beyond Skoltech, what has it been like for you to adjust to life in Russia?

Holman: Before coming to Russia, the only countries I’d been to were in Western and Central Europe, so compared with the United Kingdom, I think Russia definitely feels more different than places I’ve previously been.

The language has been a bit of a challenge. I learned some basic survival Russian and the Cyrillic alphabet before I came here. Amongst younger people, English is pretty broadly spoken, but amongst older people, that’s not necessarily the case, so you do have to know some Russian in order to get by in supermarkets and to ask for directions. But that’s fine – I think that’s part of what being in another country is all about: trying to make an effort with the language, as difficult as that may be.

That said, it’s been really wonderful to be here. At school I studied Russian history quite a lot as well, so being able to come to Moscow and St. Petersburg, and see some of the sites I studied about in school is very, very exciting. I’d always dreamt of coming to Russia on holiday but I never thought I’d have the opportunity to come work here too, so I feel very lucky and happy to be here.

Wyss: For me, the most challenging aspect has been the language, but I’ve managed so far. The most fascinating part has been how big it all is. It’s nearly twice the size of London, and I feel like London is quite huge. I’m really looking forward to exploring the touristic sites while I’m here. Apart from that, I do not feel like huge readjustments are necessary when moving to Moscow, or at least not much bigger than when moving to any other city. I can only recommend coming to Moscow and discovering it, but make sure to freshen up your Russian beforehand!